A bridge, culvert, the road nearby or above, the banks, and the surrounding ecosystem are affected by water’s flow. It is no surprise, then, that studying hydraulics and hydrology when designing bridges is paramount for safety, road users, and engineers.

The purpose of hydrology is to study water itself with respect to the land, whereas hydraulics studies what the water is doing within a channel or pipe. So, when engineers develop 2D hydraulic models, they are looking at how water behaves in a given area, and ultimately use that information to build safer bridges. This type of modeling tells engineers not only where the water is going, but where it wants to be.

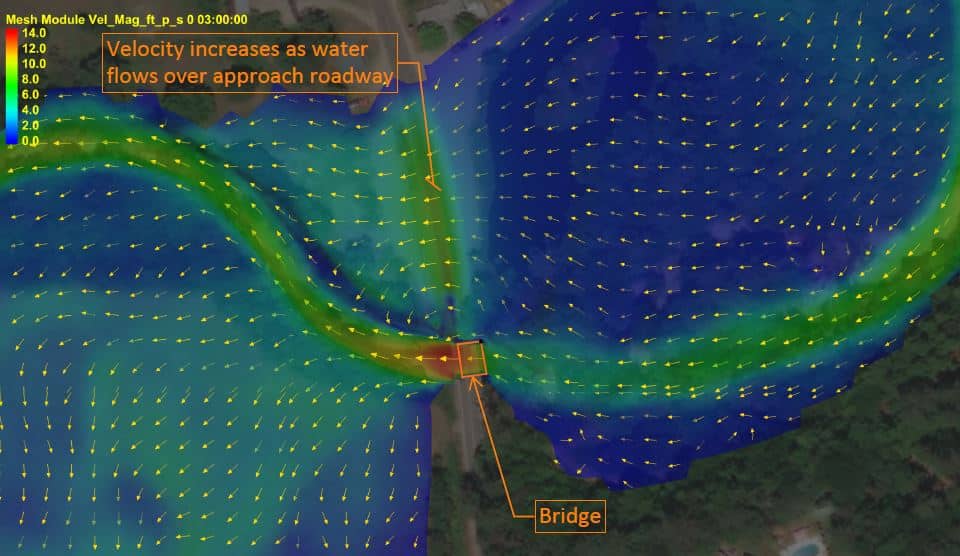

Basically, 2D modeling determines and depicts water flowing back and forth (on a horizontal plane) instead of horizontally and vertically (3D modeling). The modeling is presented as a dynamic graphic that shows the flow of the river or water body. With a bridge in the model, engineers can determine how the water will move around piers and abutments (the bridge foundation), what could happen with scour and decide how to design for it, and predict the bridge’s impact on the environment (and the environment’s impact on the bridge) for years to come.

First things First

When a bridge engineer designs a bridge or culvert associated with water, hydraulic modeling isn’t an afterthought; it’s one of the first things that gets done when a project starts. Structural engineers already have data about the area and usually the existing bridge. Still, they often need more specific information to understand the entire project better – for example, data points on the lowest part of the bridge and how the structure is situated in relation to the water below.

2D hydraulic modeling at the beginning of the project gathers that information and helps the engineers better plan for the project, and is welcomed by this engineer as a preferred alternative to the conventional 1D modeling. It’s not just a benefit to engineers who want to know a system’s details, though. Clients, municipalities, and everyday citizens benefit from engineers using 2D hydraulic modeling – because it helps convey to them what’s happening with the water and helps the engineers better protect the infrastructure we use every day.

When it Rains, it Pours

When you think back to the Mother’s Day floods in 2006 or any other time flooding threatened New England, you probably don’t think much about the bridges you drive unless the water pools over the road. What few people think about is what’s happening under and over the bridge; with faster rushing waters and more force, there’s the potential for three big events: scour, rising water carrying debris, and pressure on the bridge caused by flooding water.

Scour is what happens when sediment around the bridge foundation (or along the roadway) erodes and starts washing downstream, leaving the potential for the material under the bridge to become unstable. In some cases, sediment from upstream of the bridge will wash downstream and fill in these holes during the storm before anyone realizes how big of a scour hole actually developed. We use 2D hydraulic modeling to help better predict the scour that might occur during these events even though we may not see it.

This erosion can also occur beside and/or below the roadways leading up to the bridge if the water flows over the roadway. The 2D model enables us to see how much of the water is going over the roadway as well as provides us with the depth and velocity of this water. We can use this information to determine if the sides of the roadway might be in danger of washing away with the water. If the embankments might erode, we can properly armor them and keep them protected.

Part of our job is looking out for this erosion – if we determine that scour might be a potential issue during a storm, we can get ahead of it. One way of doing this to help prevent it under the bridge is by putting riprap (larger stones) in front of and around the bridge foundation to help keep the natural, finer sediment of the streambed and below the foundation in place. Another way is potentially changing the foundation type: if the anticipated scour is deep, we might change from a shallow foundation to a deep foundation. Scour is just one of the dangers associated with large storms, and 2D hydraulic modeling gives engineers the insight they need to help prevent dangerous situations.

Rising water is another danger to bridges, not just because it could potentially overtop (flow over) the bridge, but because the rushing waters can carry debris (say, a fallen tree) that could hit the bridge and cause damage. When we plug in potential flooding scenarios into the 2D hydraulic models, we use the models to predict how high the water could potentially get during a storm. That way, we can plan to build a new bridge or raise an existing bridge above the water level, reducing the chance for the bridge to be damaged.

The third big concern with large storms is the power of flooding waters pushing on the bridge. This pressure could be going into and on top of the bridge, but also could come from under the bridge (buoyant forces trying to lift the bridge up). For this scenario, 2D hydraulic modeling allows us to see where the water would want to go during a flood and determine how much of it is going under the bridge, over the bridge, and around the bridge. This allows us to evaluate what an existing bridge might experience, and to design a new bridge to eliminate these forces (locate the deck above the water) and to resist the forces that can’t be eliminated for a certain storm event.

Garbage in, Garbage Out

The more data we can put into the model and the more accurate that data is, the more confident we can be with the results. That means that for the most part, 2D hydraulic modeling provides valuable information that we had to assume or make educated guesses about 30 years ago. While 2D hydraulic modeling doesn’t solve every problem, it gets us closer to understanding the hydraulics of the bridge. In the event that a solution doesn’t quite make sense, it could be because we need more or better data to put into the 2D hydraulic model.

For example, we’re working on a project right now that is analyzing an existing bridge in a river. Using 2D hydraulic modeling, we noticed that the water isn’t flowing as expected. We looked upstream and noticed old bridge abutments causing a constriction in the water flow. This slight constriction causing the river to backwater and holding part of the flow back is a great example of how limited data can affect the hydraulic modeling, or what I like to call “garbage in, garbage out.” If we didn’t have the data that depicted this constriction, we might have missed how it influences the river and the flow at our crossing.

Another project currently underway involves an upgrade and analysis of two culverts, with a third culvert right upstream, that have all been causing water constriction. The 2D hydraulic model shows us how these constrictions are causing backwater and increased flooding. The 2D hydraulic analysis also allows us to see what happens when we change the structures in the water. With some tweaks to the 2D model, we’re able to see that if we replace the two downstream culverts with a wide open structure that spans the bankfull width, the flooding is significantly reduced in the model. Meaning that if we replace these culverts with this other bridge system we designed, the next huge rainstorm won’t cause so much issue.

Want to know more about 2D hydraulic modeling?

We’re only as good as our data and our engineers’ analysis of that data. 2D hydraulic modeling has helped us foresee challenges to certain bridge structures while advocating for others to serve an area better. It replaces 1D hydraulic modeling at a time when computers now have the bandwidth to handle the massive programs required to use.

If you have any further questions, reach out to me and stay tuned for the follow-up blog on the different programs and math needed for this undertaking!