In my career as an environmental scientist, with a focus on permitting and regulatory compliance, I review projects for the potential to affect species that are protected under the Endangered Species Act and assist our clients in understanding how their project can be revised, when necessary, to avoid or minimize impacting these species or their habitat while still meeting the project goals.

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) was enacted in 1973 as one of the several federal laws passed in the 1970s to address the rising concerns about environmental protection. The intentions of the ESA are to protect and prevent species from becoming extinct, prepare and implement efforts towards recovering species that are trending towards extinction, protect and preserve the ecosystems and habitat on which these species depend, and provide for cooperation among state governments to assist in these efforts on a regional and local level.

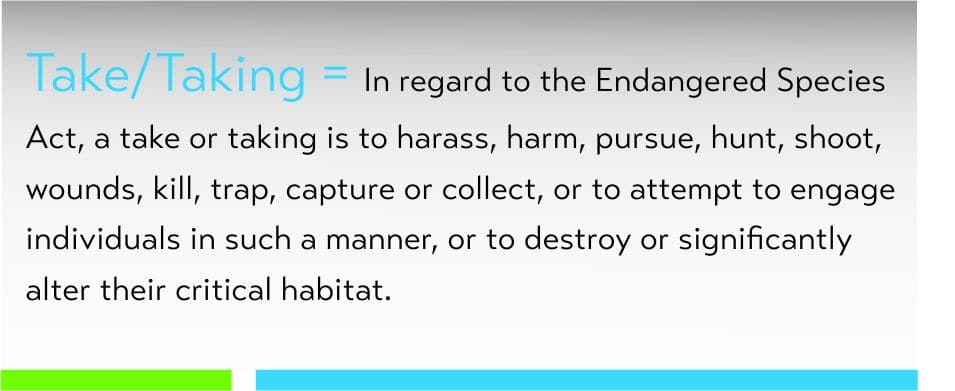

If this seems like a very large task, it is indeed! There are three different federal departments that administer the ESA: the Department of Interior (endangered animals and some plants), the Department of Commerce (marine mammals) and the Department of Agriculture (plants). Between them, over nearly 50 years, they have developed regulatory guidance that breaks this large effort down into some very specific actions and processes. They develop the official list of endangered and threatened species and enforce rules regarding the import, export, take, possess, selling or transporting any endangered or threatened species. In addition, they develop detailed descriptions and mapping of the critical habitat for listed species, including land that is presently occupied by the listed species and land that is important for its continued and future existence.

Creating The List

At the start of the process is The List – how to determine which species belong on the list and deserve the protective efforts of federal organizations? This can be a controversial topic, as critics of the ESA often say it targets the “fluffy” or “cute” species, or those that pull at our heartstrings like the Florida panther, Monarch butterfly, North Atlantic right whale, Green sea turtle. (You may also think of pandas, but we do not have pandas in the wild in the US!) You may not think the Ozark hellbender, the meltwater stonefly or the Atlantic sturgeon, all worthy of protection despite their lack of photogenic features, but these species are considered just as important as any other federally-listed species.

The biggest challenge is that we cannot protect all organisms; the financial realities are that budgets must be created to pay for enacting all of the sections of the ESA – someone needs to conduct surveys, develop Critical Habitat Plans, provide assistance in protection and enforce the rules when they are broken. It is up the federal agencies, then, to determine in a real-world way which species are essential to protect. The lists must be made based on valid science, and not swayed by popular opinions of which mammal is more huggable. And while there is certainly a school of thought that saving only certain species is by its very nature a flawed process, one must start someplace. Saving some is better than saving none.

Species are often identified for protection because that species is an indicator of the status of their ecological surrounding or is key to the regional ecological cycle – these are sometimes called “keystone species.” The sea otter, very cute and cuddly, is a great example – they feed on sea urchins, and when sea otter numbers fell due to demand for their pelts, sea urchins boomed and munched their way through acres of kelp beds, which altered the ecosystem for the other fish and marine life dependent on the kelp forest microhabitat. Protecting the sea otter then protects a variety of other species. As another example, less cuddly, the Florida bonneted bat lives in the native forests of Florida and is a valuable source of pest control – reduction in their numbers has resulted in the need for additional pesticide use in those areas.

Another concept is to protect “umbrella” species, like the Florida panther, which has a home range of several hundred miles in which it routinely travels. Development of new roads can fragment what are currently large blocks of contiguous habitat that allow for safe travel for panthers, so some protective measures include land use controls that are focused on reduction of expanding land development into these unfragmented areas. Leaving large areas unfragmented and undeveloped allows for protection for all of the other species that also live in these areas. In that way, the umbrella that covers the panther also covers other species.

Decisions, Decisions…

But there is also a consideration of the fiscal realities and physical practicalities:

- What are the measures necessary to save a species, and can we afford to?

- Are some species too time-consuming to protect?

- Is that species worthy of affording all of the time and effort spent preserving it?

- Will it work? Will the effort to protect a single species result in other losses in areas that are important?

This circles back to the emotional potential for saving species that are “fluffy” and look nice on a brochure asking you to donate to the cause. These “flagship” or “charismatic” species are the celebrities of the natural world, and by pulling our attention to the plight of such species, organizations can educate and raise awareness for conservation of all protected species and natural areas. Which means that the fluffy species have a role to play.

What Can You Do?

If you can contribute to wildlife organizations, do so – time or money donated on behalf of fluffy species can benefit other species. But consider donating to organizations that actively support conservation measures for the “ugly” species, too, or to local land or wildlife conservation organizations. If you are working in land development, understand how the ESA requirements apply to your project, and be proactive in meeting those requirements. Hoyle Tanner’s team of environmental scientists is always prepared to work with our private, municipal and state clients to successfully address the ESA while advancing the needs of the project.